Nobody asked, but I just wanted to say that no artist matters more to me than Sleater-Kinney. I offer this unsolicited piece of personal trivia if only to (necessarily) oversell this otherwise mildly exciting news to many: The band is back with a new song titled “Worry With You” along with news that they will be dropping a new album called “Path of Wellness” on June 11 this year. It’s their follow-up to 2019’s “The Center Won’t Hold,” an ambitious synth-heavy record that predictably polarized listeners due in part to its supposed departure from the band’s raw, guitar-and-drums setup. The St. Vincent-produced record is also the last one featuring Janet Weiss, Still The Best Drummer In Indie Rock.

I’m still trying to figure that album out, but the most honest, impartial thing I can say about it is that just like the rest of their discography, you can’t assess it based solely on the rigid good-or-bad dichotomy. It is extremely easy to fall trap to these reductive assessments—deciding whether a record is, simply, “good” or “bad”—but the genius of Sleater-Kinney lies in their unyielding rejection of easy definitions, of complacency and comfort, all without losing touch with their roots. Hence, 19 years of genre-traversing, politically charged rock that illuminated what it means to be queer and feminist and human. Of course, in the context of early music journalism and the sacred rock canon, that means constantly outdoing yourself for close to two decades so as to render the singularly stupid question, “what’s it like to be an all-female band?” irrelevant.

Sleater-Kinney is (mostly) way past that point in their career, and not that they needed permission or for the natural sobering properties of time to nullify the shock value of queer stories set against “unpalatable” music, but “Worry With You” feels like something of a reaffirmation of—a virtual lesbian salute to—what the band stands for. I may or may not be pertaining specifically to the music video, which follows a queer couple at home amid, presumably, the COVID-19 pandemic. The two women are living in close quarters, and so they obviously vacillate between loving and hating each other. But the point, as the song rather unsubtly spells out, is that even if things are shit, at least they have each other—which is probably the most you can ask for during a time of unprecedented longing and loneliness.

It’s a neat little indie rock track that has the trappings of a standard Sleater-Kinney song: Carrie Brownstein’s hiccupy, heavily cadenced vocals set against the interplay between a Stella Bagcan-esqe-slash-Gang of Four-type guitar riff and Corin Tucker’s bass-like guitar. It’s one of their more pop-leaning songs, not by way of “All Hands On the Bad One” choruses, but of a new sonic sensibility that is aware of the music now and the meaninglessness of labels like poptimism or rocktimism or whatever.

Sleater-Kinney have always been masters of distilling messy feelings into potent and cohesive things; sonic monoliths that hit you and remind you to keep resisting and questioning. We need more of that this year; and the next, and the next.

Writer: Catherine Orda

Photo screengrabbed from the “Worry With You” music video

Follow Preen on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube and Viber

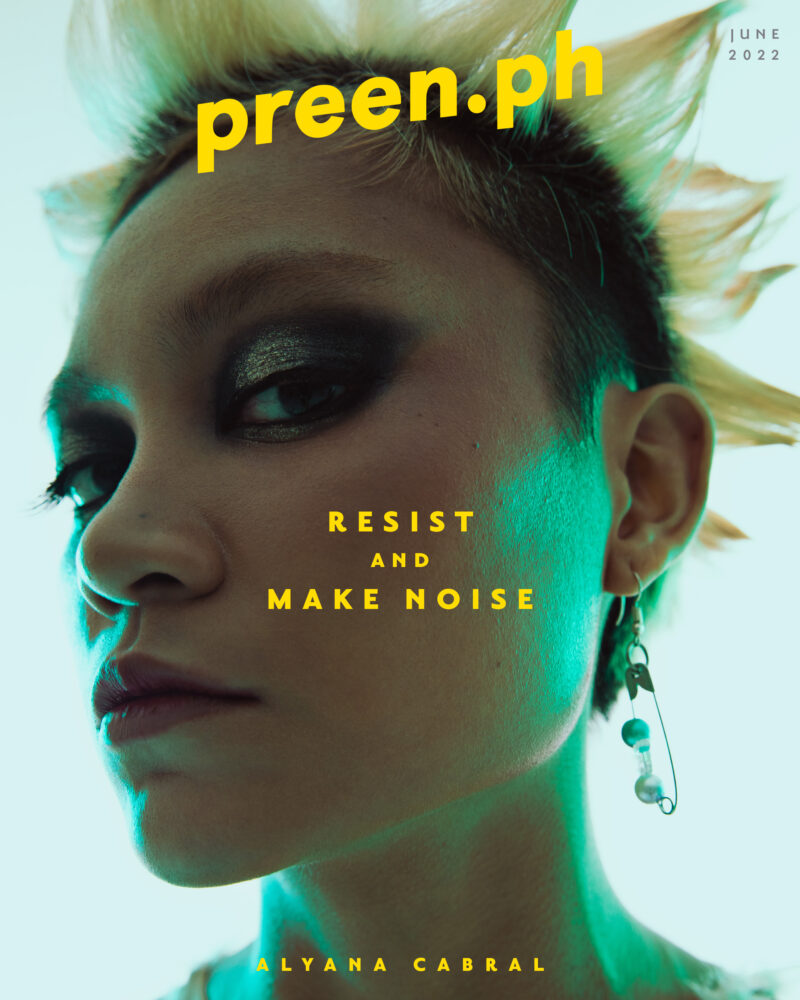

The first time I saw Alyana Cabral play live was the last time a number of us would go to a gig unaware of the nightmare that would take over in the next few years. We had lined the cramped basement of Mow’s in Quezon City that night, surrounding whoever’s turn it was to play. When Cabral finally took her place, it wasn’t unlike the experience of sitting across her on a couch two years later as she tells me what she’s been busy with these days.

Working as the resident DJ of Dirty Kitchen, playing sets in different bars and clubs, and making experimental electronic music, Cabral has lately been focusing on her solo project, Teenage Granny. The differences between this project and the music she makes with her bands, arguably what more listeners know her better for, are stark but not worth dwelling on. They all have a piece of Cabral anyway, that same timber of calm urgency and swell of energy that color even her quieter songs.

Of course she was just doing what musicians have always done, which is to turn life into sound. But here is a queer young woman singing about one thing in so many ways, and for whom politics is the inescapable condition rather than a matter of definition (read: the tired question,“Does art have to be political?”), and that should free listeners of the burden of uncertainty, the false comfort of complacency.

“Hindi naman masamang sabihin na political ’yung music or art. It’s actually just… it’s really what it is. Ganun talaga siya umiiral. And when you accept that, the question now is, what’s the next move? How do you move forward after accepting that art is political? Especially since we’re living in a very crucial moment in history na ang daming nangyayari na paulit-ulit na mga kababalaghan sa pulitika,” she says.

What is the next move if movement can only happen within and against a space built on the worsening interwoven problems of fascism, patriarchy, and misogyny?

In 2021, Cabral contributed to “Pasya,” a 12-track album spearheaded by the Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights, which advocates the destigmatization and decriminalization of abortion in the country (the procedure remains illegal in the country, and because access is highly limited, about 1,000 women die from unsafe abortions every year). As a peasant advocate and feminist, the musican also worked as an organizer and co-convener for SAKA (Sama-samang Artista para sa Kilusang Agraryo) and as one of the co-founders of Kababae Mong Tao, a multimedia platform that empowers women creatives.

You make art and try your best to reflect and change realities, and then you also don’t.

“We know that art on its own is never enough. It’s a question of being aware of how whatever else it is that you do can contribute to and reflect resistance,” Cabral says.

Throughout our conversation, the musician is evidently conscious of the scope and weight of the themes of her work (“I write about the struggles of being a woman. The struggles of being a queer woman in a third world society. Or how I interpret the sociopolitical climate at the moment”) and of the conversation itself, but this isn’t a problem.

Cabral treads these connections effortlessly, so that by the time I ask her which female artists she turns to for inspiration, it seemed only fitting that she talked about them in the context of her own disillusionment with female and queer representation in the music industry. “Marami akong kakilala who have male figures as inspiration kasi nagkukulang sila ng female figures to look to because of how media portrays men and women. Siyempre may gender imbalance pa rin,” she says.

“When I was on my journey to becoming a feminist, I became more aware of these things, which is why I started to look for more inspiration in women. Not to say you shouldn’t do the same with men, but just to balance out my expression and see other perspectives and artists that are not highlighted in media.”

“I call it pure love energy. I think ’yun ’yung queerness, that’s where it lies. That’s how I express queerness in music—by tapping into that source of pureness and love and bliss.”

Inspiration and influence aren’t purely musical for Cabral, who, if it isn’t clear by now, seems to be one of those people for whom intersectionality and in particular the interdependency of things are a given.

“Kailangan ko ng model or example not just in music but also when it comes to being a feminist or looking for values within myself and within my community. In being a feminist, it’s important to be able to recognize female and queer artists who are overlooked and underappreciated,” she says. I ask her to name some of them.

“Sige, mag-name drop ako [laughs]. My mother, first and foremost. ’Yung Elephant community here in Manila, queer musicians and DJs.” Cabral is careful not to miss any names, settling on a few more who have been instrumental in her music and activism: AGF or poemproducer, an artist from Finland who makes sound art and experimental music (“She has an archive called female:pressure na nandoon lahat ng women pioneers of electronic music”), Joee & I (“my friend Joee [Mejias]…siya ’yung Bjork ng Pilipinas”), Fempop network of feminists, and Heresy.

“Alice Coltrane. Madonna [laughs].”

More than these names, spaces and communities have played a big part in making Cabral’s queer expression possible. The promise of a community backing you up and making you feel like you’re never alone sounds like the vaguest of dreams, but when it happens, there is nothing like it. When I ask Cabral about how she came to terms with her own queerness and how finding a community was a factor in that, she briefly details the kind of family dynamic that every queer kid would wish to grow up around.

“I was lucky that I didn’t have so much of a hard time being accepted by my family. I didn’t need to come out to them. And feeling ko ’yung journey ko of discovering my queerness is intersectional with my journey of my art expression, of discovering myself as an artist. Parang magkadikit din ’yun for me: being queer and a creative person. ’Yung struggle ko was I had to go through a lot of painful relationships in my early 20s. I had to go through all that to be able to realize how I identify, but now I’m in a good place.”

I ask her what the best part about being queer is. “The feeling of…wala na ’kong pake kung anong tingin ng ibang tao sa ’kin. Parang, bahala kayo diyan, this is me. Ako lang ’to. [laughs]. Feeling free about who you are and how you express yourself and being able to experiment with how I give and receive love and attraction and intimacy.”

When she starts talking about community, Cabral is clear about not just the good that comes with belonging, but more importantly on what those privileges obligate her to do. She tells me that now she is more focused on trying to fight for her peers whom she knows are having a harder time than she is, on making sure she paticipates in the queer communities she is a part of.

Besides her activism, her more explicit acts of resistance, how else does Cabral resist? The unspoken custom that queerness exists (and in a way, thrives) in subtext isn’t lost in Cabral’s work, and though I pined for the opposite—visibility, directness—she spoke of another possibility that seems, at least for now, worth pursuing. It isn’t about hiding, it isn’t about appearances at all.

“It’s [queerness] in the soul. That’s how I approach the queer aspect of my work. In the spiritual world, wala namang gender. And ’yun naman talaga ’yung end goal ng queer struggle, ’di ba? To completely abolish gender.”

“I’m trying to reach for that place or dimension where queerness is in its purest and ultimate form. It’s this thing that I try to incorporate in my work. I call it pure love energy. I think ’yun ’yung queerness, that’s where it lies. That’s how I express queerness in music—by tapping into that source of pureness and love and bliss.”

Photos by Joseph Pascual

Story by Catherine Orda

Styling by Edlene Cabral

Makeup by Dorothy Mamalio

Hair by Mong Amado

Creative direction by Nimu Muallam and Neal Alday

Produced by Zofiya Acosta

Follow Preen on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Viber

In E. San Juan Jr.’s “Sisa’s Vengeance: Jose Rizal’s Sexual Politics and Cultural Revolution,” the literary scholar presents a radical reading of Rizal, arguing that the novelist did in fact believe in gender equality as key in the fight for national liberation.

A feminist reading of Rizal is radical (and most welcome) for several reasons, and San Juan makes a compelling case by reading the character of Sisa as the embodiment of the injustices suffered by the motherland.

But our literature has long harbored these connections, even beyond love stories set against the backdrop of revolution. Which is to say that Rizal’s critique of colonialism as found in the fate of his female characters may just be a welcome addition to the long line of Filipina authors writing the story of their nation.

The Manila Critics Circle and the National Book Development Board recently announced the finalists for the 40th National Book Awards—many of them authored by women whose contributions to literature have shaped our culture. Here are the titles we’re rooting for:

1. “Solo Flight: Mga Kuwento” by Rita dela Cruz (Isang Balangay Media Productions, 2021)

Published by Balangay Books, Rita dela Cruz’s collection of stories is a meditation on being alone, in particular what it is like to be a single woman—whether by choice or circumstance—in a society where this is stigmatized. Introspection is a reliable and comforting companion in these deceptively simple stories that feature very human characters, which, told in a familiar and easy-to-understand language, evoke intimacy by way of relatability.

The dynamics of female friendships also figure heavily into Dela Cruz’s stories, particularly how women in similar situations find in each other a kind of respite from the pressures of being a woman. The description on its publisher’s website puts it better: “…isang selebrasyon sa pag-iisa at pag-iisa ng mga kababaihan.” Here’s to hoping we see more books like this published.

2. “What I Wanted to be When I Grew Up” by Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo (University of the Philippines Press, 2021)

Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo’s work is unparalleled for many reasons, not in the least of which is the fact that it has consistently covered both literary creation and scholarship, often featuring the life and work of women authors or deals in some way with the life of women. In “What I Wanted to be When I Grew Up,” she writes about how the books she read and the movies she watched in her youth were instrumental in her own development as a writer.

This book narrates Pantoja Hidalgo’s coming-of-age story, part of which is told through revisiting her mother’s unpublished memoirs and journals, which, as Pantoja Hidalgo’s longtime readers will recognize as material that found their way in her fiction and nonfiction.

In these memoirs, told in Pantoja Hidalgo’s distinct voice—clear, elegant, and always with a touch of wit and grace—we see a compelling portrait of one of our pioneering writers who, since her youth, her formative days as a university student and as a professor, have always found a home in reading and writing.

3. “Partial Views: On the Essay as a Genre in Philippine Literary Production” (De La Salle University Publishing House, 2021)

Although arguably better known for her poetry, Conchitina Cruz has also written significant pieces of criticism, notably on literary production in the Philippines. Her 2021 monograph tracks the development of the creative nonfiction genre in the country, and makes a case for the expansion of the perspective and obligations of the essayist: that their essays, however personal they may be, must employ the kind of accountability and self-reflexivity usually demanded from journalism and scholarly work, respectively.

Although intended for teachers and students of creative writing and literature, Cruz’s monograph proves to be a worthwhile read for anyone who might be interested in the inner workings of literary production (meaning, the politics and aesthetics that govern it) in the country.

4. “Tingle: Anthology of Filipina Lesbian Writing” edited by Jhoanna Lynn B. Cruz (Anvil Publishing, 2021)

When considering the state of queer writing in the Philippines—or anywhere in the world for that matter—it always has to do with lamenting either its lack or the absence of proper representation. Queer anthologies by design, then, almost always have an impossible task ahead of them: to fill a gap and to do so properly.

Tingle isn’t exempted from these expectations, and we are convinced that the only way to truly access its gifts beyond tokenism and the short-lived results of advertising is to actually read it. Make what you will of the stories and poems written by women whose voices are clearly missing from the mainstream. The women in this anthology are making themselves visible (in itself a powerful act) on their own terms. We hope readers will see the value in that and pick up this book.

5. “Kilapsaw” by Ellen Sicat (University of the Philippines Press, 2021)

The stories that the novelist Ellen Sicat writes, most of them dealing with family dynamics and domestic life, are always deeply attentive to the society they portray. The plot-driven Kilapsaw takes an unflinching look at gender-based violence and other harsh realities women experience in relationships. In narrating the life of Diwa, Sicat writes with restraint, which allows her the space to perform a thoughtful examination of a societal ill that is rarely given the serious attention it deserves. The predictability of the overall plot doesn’t take away from the subtlety of the project as Sicat situates her story in its proper context: a society in which notions of morality are tied with modernization, and where sexual politics and class are inextricable from everyday life.

Art by Ella Lambio

Follow Preen on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Viber

“My works are always a course correction for the adolescence I wish I had,” says Samantha Lee, who makes coming-of-age movies about girls who love girls.

In 2016, Lee made her directorial debut with “Baka Bukas,” whose main preoccupation was the aftermath of coming clean about your feelings for your best friend. Although met with mixed reviews, the Jasmine Curtis starrer put Lee on queer girls’ radar: Finally, a director who seemed bent on telling sapphic stories that didn’t end with either of the lead characters dying or suffering some other tragic fate. An online series and three films later, some considered Lee to be the face of Philippine sapphic media.

View this post on Instagram

Such sensationalist talk partly speaks to the lack of (explicitly) lesbian stories onscreen, but I personally didn’t mind hearing every few years that Lee was working on a new movie.

Last August, she put out “Rookie,” a volleyball film about an awkward transferee and basketball player named Ace (Pat Tingjuy) who, despite never having played volleyball, gets recruited to her new school’s volleyball team, the San Lorenzo Angels. There, she falls for its captain, Jana (Aya Fernandez).

The enemies-to-lovers romance blooms in an all-girls Catholic school, where the insidious sexism and homophobia of religion and patriarchy occasionally reared its ugly head—otherwise, the film is pure queer bliss and sportsmanship and female friendship.

Though far from perfect, it might be Lee’s most technically accomplished project yet: well-paced, beautifully shot, and consistently fueled by such a palpable dynamic energy, which was most evident in the final volleyball match. It also helped that Lee understands the rhythm of queer romance. The longing glances and banter punctuating the prolonged charged silences between Tingjuy and Fernandez made for a proper, highly watchable rom-com.

But at the heart of it was a tender feminism. Watching “Rookie” in the cinema was a very specific kind of joy for a specific kind of viewer: girls who lived through the peak of intrams crush culture, girls who probably wouldn’t mind a course correction for an adolescence made fraught by casual homophobic rhetoric and lesbian invisibility.

Making the country’s first volleyball film

One afternoon, the writer Natts Jadaone chanced upon a college volleyball match on TV. The heated exchanges and display of talent would make her a fan of the sport and eventually become the inspiration for a short film idea.

View this post on Instagram

“Two girls on opposing teams communicate with just glances, movement, and swagger. After the final buzzer sounds on the game, they shake hands and part ways. The romantic tension and their yearning are palpable, but they know their love is forbidden,” she writes. Soon, Jadaone’s sister, the award-winning writer-director and producer Antoinette, would ask Lee if she would be interested to direct the story that would soon become “Rookie.”

It happened that Lee had a similar story to Ace’s: She was her high school’s basketball team captain, and when she had to move to a different high school at one point, decided against the school that only had a volleyball team. “‘Rookie’ is what would have happened kung lumipat ako sa school na walang basketball team, tapos forced ako maging volleyball player,” Lee said in a podcast with Antoinette Jadaone.

In 2021, Lee and Natts Jadaone’s film was announced as one of the selections for the third edition of Full Circle Lab Philippines, a development program co-organized by the Film Development Council of the Philippines. The year after that, “Rookie” joined the official lineup of finalists for Cinemalaya 2023; capping off 2022, Lee and Project 8 Projects (Antoinette Jadaone’s production company, which co-produced the film with Anima Studios and Kumu), put out a casting call for the role of Ace: “At least 5’6. Plays volleyball. Lesbian/Bi/Queer female. Acting experience preferred but not required.”

Tinjguy, an architect and volleyball camp coach, sent in audition materials after the prompting of a friend. Tingjuy got an audition, where she was paired with Fernandez.

View this post on Instagram

“Fast forward, a month [after the audition], I got a text from Ms. Ava of Project 8 Projects asking if she could call, and she brought me the news saying I got the part of Ace. I was really happy but I couldn’t believe it. I had to ask her “Totoo po ba?” three times in that call. I thanked her and asked again ‘Sure po kayo?’ [laughs] That’s how I got the role.”

It’s hard to fault the first-time actress’s performance. Aided by just two weeks’ worth of acting classes and basketball training, Tingjuy radiated an all-too-familiar awkwardness that slowly morphed into charm, impeccable comedic timing, and vulnerability.

In a scene involving a horrifying incident with their volleyball team’s physical therapist, Ace runs out of the school crying in anger and desperation. It’s the first instance in the film where the character is allowed a cathartic moment. In shooting the scene, Tingjuy says: “I was mostly thinking that I didn’t want to be a burden to everyone. The day of the shoot, thankfully my acting coach was there. She would remind me to breathe and recall our workshop. Direk Sam also ran me through the scene saying, ‘Sa part na ‘to dapat parang naghahanap si Ace ng someone na makakatulong sa kanya pero wala siyang mahanap.’ Somewhere along those lines.”

For her part, Fernandez is equally compelling as the talented, brooding team captain. We’ve seen stories like Jana’s many times before—an overachieving, repressed only child burdened by their parents’ expectations—but Fernandez commits to the archetype with such intensity and self-possession you can’t fault Ace for falling for such an obvious choice. It’s also just a classic GL trope at play, and the chemistry between the two actresses sells it so well.

Audiences have called the film simple. It is. But that simplicity is partly deceptive given that it quite inevitably had to cover so many things: the levity of young love and the violence of patriarchy, the kineticism and logistics of the sport. With the film being shot in just nine days, the latter proved to be one of the more challenging aspects that “Rookie” had to get right. Tingjuy says that playing in front of a camera was a “long process” as “there were a lot of technicalities to consider.”

“It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my career so far. There’s just so much that needs to be captured in a little amount of time, compounded with the pressure of volleyball being one of the most beloved sports in the country. There was a lot of pressure to get things right,” says Lee, who took a lot of inspiration visually and score-wise from “Haikyu!!” “For the rest of the film, I wanted it to feel like ‘Ribs’ by Lorde,” she adds.

View this post on Instagram

By now, even those who haven’t seen the film yet might have already heard about the cameos of certain Philippine volleyball icons. Ara Galang and Tots Carlos are camp counselors. Alyssa Valdez delivers a speech she wrote herself for the Angels. The sport has obviously always had a massive following, a devotion that arguably reached new heights in the past 15 years because of players like Valdez.

“Rookie” is the Philippines’s first ever volleyball film. Its potential as a story hinged largely on the country’s love for the sport. That it was told via a queer, female-centric film, its portrayal of men either visibly minimal or secondary to the main plot, speaks volumes against the gendering of sports, in its small way reclaiming a space for women in male-dominated spaces.

“As the film’s potential started to take root, my five-year-old niece suddenly told me she wanted to be an athlete. When I asked what sport, she said volleyball, because it’s for girls and basketball is for boys. I then realized how these gendered ideas form at such an early age and questioned if we want to continue perpetuating these misconceptions,” wrote Natts Jadaone.

Queer joy, out in the open, in broad daylight

“Rookie” was one of the big winners in this year’s Cinemalaya, bagging the Best Editing Award, the Best Actress Award (for Tingjuy), and, as with all of Lee’s works, the Audience Choice Award.

View this post on Instagram

“From a very practical standpoint, winning this award is a good way to show producers that films like this can be a good investment and they should continue funding projects like these. That’s the very practical, non-emotional answer. If I were to truly wax sentimental about winning awards like this, I make my films to speak to a very specific kind of audience and to be able to receive that love and appreciation back is the only validation I ever truly need,” says the director.

We’re obviously still at a point where making any kind of queer media, because of its rarity and clear departure from heteronormativity and its institutions, is expected to be either a radical statement (though it often tends to be) or the be-all, end-all of what it is like to be queer.

From Lee’s growing filmography, which is mostly aspirational and specifically attempts to normalize queerness, it seems that one way to complicate the criticism and public discourse surrounding queer narratives is to make (and fund) more of it—quality and intent intact, needless to say.

View this post on Instagram

That, and “hold[ing] cishet people (especially men) up to the same standards just to make the playing field a little bit more equal,” says Lee, who, like any other queer woman filmmaker, on top of the actual work that goes into making films, has also had to think doubly hard about the implications of all their choices, especially when it comes to casting.

“In an ideal world, we would be living in a society where there are tons of out queer actors that we could cast for these roles. But we do not (just yet). There was a recent conversation I had with someone who said that she was a really big fan of ‘Baka Bukas’ and how that film helped her through some tough times in her coming out journey, but she followed it up with ‘are you ever going to cast queer actors for queer roles?’ And I was kind of taken aback by that question in the sense that I can keep casting queer actors for queer roles but the responsibility to make these works known shouldn’t fall solely on my shoulders… I think that a bigger burden should be placed on systems and audiences that still give importance to seeing celebrities on-screen.”

As she makes more films, the necessary compromises inherent in the business of making films are impressed repeatedly on not just queer filmmakers like Lee, but for anyone trying to make “unconventional” movies without any big-name stars. Not surprising. Still, it’s worth saying: A film like “Rookie,” although emerging as the second highest grossing film in this year’s Cinemalaya, could have earned so much more, could have reached so many more audiences.

I wish more queer kids got to witness, besides the collective squealing in cinemas, these positive little inserts that the volleyball film is filled with: Ace’s mom handing her a suit and tie instead of a dress to wear to prom, the Angels cheering on Ace and Jana as they share a kiss on the court, out in the open.

Art by Ella Lambio

Follow Preen on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, TikTok, YouTube, and Viber