This column may contain strong language, sexual content, adult humor, and other themes that may not be suitable for minors. Parental guidance is strongly advised.

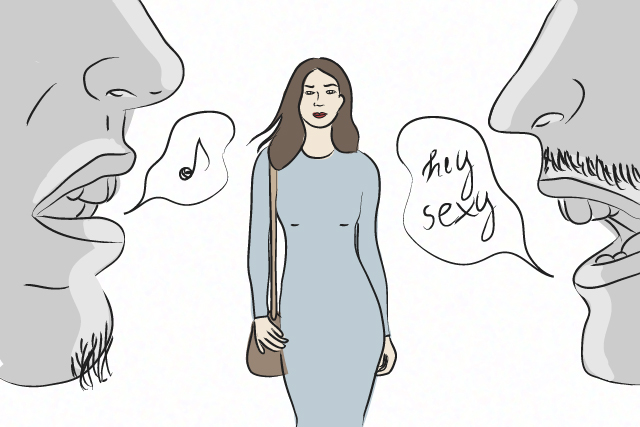

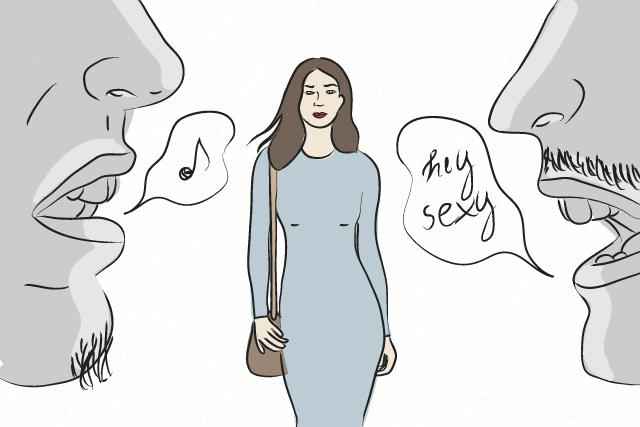

A few years ago, walking along the streets of New York City, my mother was apparently running a mental tally of men who walked past us with a compliment or a wolf-whistle directed at me. She was rather miffed that I, then in my late 40s, seemed to still be able to attract appreciative looks and comments, not to mention less polite leery glances and catcalls, from the opposite sex, men of varying ages and ethnicities and degrees of hotness; men in smart suits, men in worker’s overalls, men in uniform, men in casual attire; men who seemed prosperous and sophisticated, men who were plebs.

It didn’t matter to her who the men were or where they came from. It mattered that they noticed me and chose to express, completely unbidden, their appreciation of my looks. It mattered that they noticed me, despite the fact that I was of an age that would indicate that I was not exactly in the first—nor second—blush of youth. It mattered that decades before, men had often expressed, completely unbidden, the same appreciation of her (admittedly stunning) looks, whether in Europe, or America, or even Asia, and now she was invisible.

I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t delighted by the male attention I was receiving. It was quite flattering, considering I was a single mother of two grown daughters, to discover that I still had “it.”

So I can understand, to a certain extent, the sentiments of Catherine Deneuve, et al, the 100 or so French female actresses, writers, journalists, and academics who lamented, in an open letter to Le Monde, the indiscriminate stridency of the #MeToo movement across the Atlantic, and its accompanying mission of vigilante justice, the poisoning of relations between men and women, the politicization of something as edifyingly primal and basic as flirtation and the appreciation of female sexuality, the curtailment of sexual freedom in the in order to forward a feminist agenda that viewed men as adversaries, not partners or lovers.

“Rape is a crime,” the letter stated. “But insistent or clumsy flirting is not a crime, nor is gallantry a chauvinist aggression. As a result of the Weinstein affair, there has been a legitimate realization of the sexual violence women experience, particularly in the workplace, where some men abuse their power. It was necessary. But now this liberation of speech has been turned on its head.”

It went on to say, “This expedited justice already has its victims, men prevented from practicing their profession as punishment, forced to resign, etc., while the only thing they did wrong was touching a knee, trying to steal a kiss, or speaking about ‘intimate’ things at a work dinner, or sending messages with sexual connotation to a woman whose feelings were not mutual.”

While the letter does make some valid points—it also attacks #BalanceTonPorc, the French counterpart of #MeToo—it does highlight a very French sensibility that women of a certain generation, like Catherine Deneuve, have always embodied, a sensibility that seems to have contributed to the particular mystique that surrounds French women: that they prize sensuality and the art of seduction, that they support sexual freedom, regarding sex as being about pleasure first and foremost, that they don’t think of women as victims and abhor “self-victimization.” And that a woman’s desirability is something to cultivate, celebrate and maintain. A woman who is no longer desirable is no longer powerful; she is invisible, her value diminished.

Implicit in this way of thinking, however, is that men are and will always be the arbiters of a woman’s desirability. Even a magnificent Fanny Ardant, in her 60s, was desperate for the sexual attentions of a much younger man, who clearly was a jerk, in the movie Bright Days Ahead, because it meant she was still vital and desirable. And my 70-something mother, on a certain level, sought this same validation in New York, hoping to find it in the odd male gaze that could somehow appreciate the vital and desirable woman dressed in an elegant trench coat, who could still flirt and dazzle with disarming quips like the Catherine Deneuves of this world. I did mention to her that perhaps giving up smoking in an increasingly health-conscious America might make her more attractive.

So for all the letter’s talk about “inner freedom,” and the power that comes from knowing that “a woman can, in the same day, lead a professional team and enjoy being the sexual object of a man, without being a ‘promiscuous woman,’ nor a vile accomplice of patriarchy,” it seemed to insist on a woman’s right to be appreciated and objectified, without acknowledging that there are men who insist, equally, on appreciating and objectifying women to the point of violence, abuse, harassment, and assault.

Perhaps it’s true that women should never underestimate the power of charm and flirtation, or even sexy underwear. And women should never have to be victimized. But men should also understand and respect boundaries.

B. Wiser is the author of Making Love in Spanish, a novel published by Anvil Publishing and available in National Book Store and Powerbooks, as well as online. When not assuming her Sasha Fierce alter-ego, she takes on the role of serious journalist and media consultant.

For comments and questions, e-mail [email protected].

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are solely those of the author in her private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of Preen.ph, or any other entity of the Inquirer Group of Companies.

Art by Lara Intong

Follow Preen on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, and Viber

Related stories:

Why Do People Put Deadlines on Every Woman’s Desirability and Accomplishments?

All the Reasons Why Men Should Keep It in Their Pants

Where Do We Draw the Line When It Comes to Women’s Sexual Harassment Allegations?

Sexual Misconduct Is Never a Laughing Matter, But Why Is it Always a Joke?